|

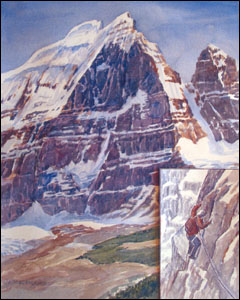

It is, hands down, the hardest face in the Canadian Rockies. Five thousand feet

of sheer, black, and north-facing limestone, steeper than the Eiger, one and a

half times as high as El Cap, a great dark cape of a peak. Hundredfoot seracs

calve thunderously from its belly, wisps of water ice hang from its brow like

icicles tacked to a ship's prow, and rockfalldarkened icefields foot its

soaring pillars. Then there is the loose rock and the falling rock... at times

it makes the Eiger look like a child's sandbox. Climbers are familiar with

almost every crack on El Cap, yet, after 30 years of

attempts, just two routes have been established up the shadowland of

North Twin; its mystery unmarred, its aura enhanced by each and every one of the

vanquished.

In the dog days of August, 1974, George Lowe and Chris Jones venture onto the

Twin in full-on Eiger Sanction mode: full-shanked leather boots, wool knickers,

Dachstein mitts, nylon tops. They find climbing similar to the hardest ground in

the Dolomites (5.10 A4) yet their situation, in what local climbers refer to

as the "Black Hole" of the Canadian Rockies, is far more serious than

any climb in the Dolomites. They are a full day of mountainous travel from the

nearest road, and once past the first quarter of the wall, rescue - even given

today's techniques - is impossible; furthermore, the wall they are on is

glaciated, vertical to overhanging, and brazed with alpine ice. The Reader's

Digest version is that there is really nothing comparable to North Twin in the

Alps. George and Chris strive; wet blowing snow frequently smears slush onto the

holds. On the fifth day they are battered by hail and George "goofs-up"

a hop step while waiting

for Chris to remove and send up a piton from the belay; George falls 30 feet and

loses the critical aid placement of the pitch. They are 4000 feet up the wall.

That night, their fifth on the wall, neither man sleeps until 3 a.m. When they

admit to each other that they no longer have enough gear to retreat and that

there is no chance of a rescue, they agree that there are no options; if they

are to survive they have to climb.

The dawn of day six brings swirling clouds and snow. George leads an improbable

and time consuming traverse across a snow-peppered slab, then escapes into an

ice runnel that he gains by liebacking the edge of a roof and pressing his knees

into the remains of the winter's snow/ice. Falling snow matures into hail,

avalanches run, George leads through the storm for 15 pitches on ice. They have

all of three ice screws. Chris and George summit and set-up their small tent

right there. Accumulating snow collapses the tent twice in the night.

Writing in Ascent Chris stated that he and George had crossed an indefinable

line. On their eighth day out, searching for the descent by compass atop the

Columbia Icefield, they caught a brief glimpse of a helicopter and heard warden

Hans Fuhrer's words, diced by the rotor, "ARE YOU OK?" "We

realized someone cared about us," wrote Jones, "that we were not alone

... tears ran down my face."

I'll suggest that, in 1974, the route that George and Chris opened on the north

face of North Twin was the hardest alpine route in the world. I believe that

nothing then accomplished in Patagonia, the Alps, Alaska, or the Himalaya

measured up to what George and Chris accomplished with "a rope, a rack,

and two packs."

Barry Blanchard

Ta članek sem opazil v American Alpine Journalu ąele po vrnitvi iz Kanade (op. Marka Prezelja). |